|

Semana Santa is coming up. Every city in Andalucía is getting ready. In the north it might be quite solemn, but here in Andalucia it is a fiesta. You dress up, you stay up, you eat well and you hang out on the streets with family and friends. It goes on all night long, all next week. One of the most striking, and perhaps most eerie, spectacles of the festival are the Nazarenos in their tall, pointy hats and matching robes with their faces completely covered, apart from their eyes. The sight of hundreds of slow-moving unidentifiable figures in these ghostly, alarming costumes can be a little unsettling, and they are frequently compared to the Ku Klux Klan. One can be forgiven for believing the Ku Klux Klan and the Semana Santa parades were borne of the same idea, since the costumes of both are practically identical. Despite this, there appears to be no connection whatsoever between the two, although the Nazarenos came first. The Ku Klux Klan used their costumes for disguise, for the Christian connotations and perhaps the fact they were usually white had a racial significance. As for why the costumes are used in Semana Santa celebrations, the origins remain a mystery but the purpose is simple – their faces are covered in mourning, and also as a sign of shame for the sins they have committed throughout the year. Somehow, though, they manage to soften the blow for spectators not in the know by the sneakers they wear visible with their costumes and the can of beer and half-smoked Ducado they are often seen carrying – a reminder that Semana Santa is, essentially, simply a fun festival in Andalusía. (I've quoted Think Spain in some of this)

0 Comments

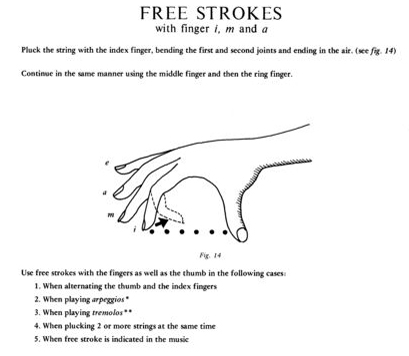

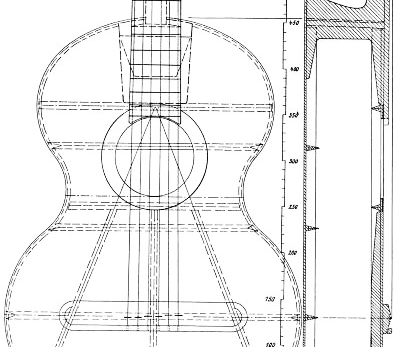

ALMERÍA'S NEW GUITAR MUSEUM Almería is east of us. It’s a nice city. Antonio de Torres was born there in 1817. After a series of setbacks he was able to produce a somewhat larger guitar, with larger template, a deeper body and the perfect fan bracing on the interior of the soundboard that literally pulses the sound outward. This is still the model for guitars today. The Spanish guitar is a Torres guitar, and now it’s in a museum in Almería to see and experience – with film and display and instruments to play.

The Guitar is played almost the world over, but its history before the end of the 15th century is a bit unclear. Most contemporary musicologists still consider its source to be the Iberian Peninsula. During the 16th century one still played the vihuela, but during the 18th century a 5th string was added to the guitar and it became very well-liked. Then, the piano, cello and violin entered the stage and was heard above everything. Time for a 6th string – and by the 19th century the guitar's popularity had increased again. Today we have the electric guitar, sound pedals, reverb, amplifiers and MIDIs, but this hasn’t seemed to quiet the acoustic guitar. HOW DOES IT SOUND? a selection (click on the photo)

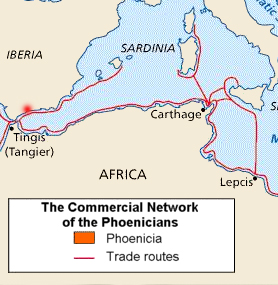

Knowledge, people and culture have always been transported over the sea, enriching & developing. Once it was the sea that united, not divided, countries and people. From the 8th century BCE the Phoenicians, antiquity’s most accomplished seaman, from what is today’s Lebanon, built settlements and trade posts from one end of the Mediterranean to the other. It made it possible to trade and communicate with different lands and peoples. Monte Testaccio, an ancient dump in Rome, is basically made of amphora, terracotta container that were used to transport olive oil from the Iberian peninsula during the first 250 years of the common era. Andalucian folk music from the mountains of Malaga, Los Verdiales, is said to have originally come from Anatolia by way of ancient Greece and Rome taken with them or by the Phoencians. Just to give a few examples. It has been about 5.3 million years since the Straight of Gibraltar opened up allowing water to flow in. This apparently went rather quickly. It took between a couple months to a couple years to flood the basin. In a few more million years it’s said that the Mediterranean will once again disappear like all other bodies of water on earth. What is in the Mediterranean? Bluefin tuna and some 700 other species of fishes, whales, dolphins, seals and sea turtles; shipwreck treasures from millennia of trade; coral reefs, wide meadows of seagrasses. However, overfishing and pollution are a constant threat. All 21 bordering countries share the responsibility, but only Spain, up to now, has adopted an IUU-plan to prevent the overexploitation and depletion of Mediterranean fish stocks to unacceptable levels. Read more about what Greenpeace suggests for the future of the sea > Cutar. photo Micke Berg

Architecture in Andalusia is as multifaceted as its history. Newsletter # 14 Feb Here everyone has stopped by, the Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Visigoths, Byzantines, the Arabs. Styles have followed each other, Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Romanticism, Modernism… In the pueblos there are certainly strong traditions – like narrow streets, white-limed facades and iron-bared windows. From the entry often a passage to an outdoor area, and the kitchen on the bottom level, while foodstuff used to be stored on the second – But in cities it’s layer-upon-layer. Mosques became churches; fish markets are becoming art museums. And, in turn, now contemporary Spanish Architecture is spreading over the world. Rafael Moneo designed Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Ricardo Bofill spectacular housing blocks in France and Sweden. Santiago Calatrava has designed public buildings in Germany, Switzerland, Argentina and recently the new train station at the WTC in New York. Spanish architecture is highly regarded. But the latest financial crisis has quieted domestic development. Some say that this is just what’s needed. Now it’s time to take advantage of the local history and create a new humane, sustainable and generous architecture in Spain. The Andalusian wave?

Everything is connected. I have a house full of books, I am not kidding. I have given books away, left them at strange places, made art of them, and used them as building material. But they still seem to multiply, and I am constantly left without enough shelve space. Most of my books are full of pictures. They are on art, on design, craft… but there are also quite a few on history, philosophy, politics, some special novels I can’t part with – and poetry. It makes me happy when I see visitors engaged in a book they've pulled out, or when they disappear up into their rooms, or out into the garden, with a couple well-chosen volumes under their arm. Books are good friends. Our very first workshops a few years ago were on Artists’ Books. There are still traces from these around the house. Last month we had a week on creative writing. Participants, and teachers, hung around the big table discussing plots, metaphors, seduction and the meaning of literature. And last week we had Kerstin here, giving lectures on the memories of Al-Andalus. While discussing the history of Córdoba - merely an hour away from Málaga - the subject of books, of course, came up. Kerstin told us about how books and papermaking spread westward across Africa to Al-Andalus, and about Al-Hakam, the famous Umayyad Caliph of Spain, and his rich collection of books that laid the foundation for intellectual study in Spain. In the 10th century Al-Hakam II opened up library after library. In addition, poets, many of them born and raised in Córdoba, had a tremendous political influence. They were treated with a respect unheard of - and, sometimes sent in exile because of their potential political danger. Córdoba with its libraries had become the intellectual center of Europe. People bought, wrote, and collected books. The libraries grew with rapidity -- even though books were still copied by hand! It is said that the city was famous for housing libraries with well over 400,000 books while having a population of 100,000, making it one of the most splendid cities in the world at the time. So, thinking about it, I take it back. I do not have a house full of books. It’s merely a drop in the ocean. But I love them all. Photo by H.Vigil. Kajsa-Tuva Henriksson´s result from workshop Artist's Books @ laCultura.

We skipped Easter this year, and took the ferry to Morocco instead. 40 minutes across the Mediterranean sea. Andalucía and Morocco may share much of their history, but Morocco is inundated with blue. The blue of the ocean and the sky have overflowed, the doors, the windows, the tiles, the boats… It is not just any blue – the shades of Moroccan blue are rich and warm, they pull towards turquoise, rather than red or violet. I buy a blue gandora and stride the streets of Safi, Marrakesh, Tangier, Essaouira with calm and with confidence. I dream about painting everything in sight in blue, blue, blue when I get back home to my house.

So what is this blue all about? I do some research and find it’s a bit puzzling. Stories interlace and contradict. Scholars write that at certain times in Moorish Spain, and other parts of the Islamic world, blue was the color for Christians and Jews, because only Muslims were allowed to wear white and green. In the Islamic world blue really was of secondary importance to green, but dark blue and turquoise decorative tiles were commonly used to decorate the facades and interiors of mosques and palaces, from Spain to Central Asia. I read that dark blue is the traditional color for good karma, positive energies and protection against the ‘Evil Eye’, and that this goes for light blue as well, with the difference light blue is also the color of the sky, so it symbolizes truth. Hence, the blue doors prevalent in a lot of places around the world, especially in the Mediterranean regions, are likely there because they are believed to repel evil. Some say it also serves as a mosquito repellant because “mosquitoes only like yellow”, and that light blue is used to mark Andalucíans homes. Blue are also the turbans worn by the men of the Tuareg people in North Africa, in protection against the sun and wind-blown sand of the Sahara desert. Instead of using dye, which uses precious water, the turbans are colored by pounding the fabric with powdered indigo. The blue color transfers to the skin, where it is seen as a sign of nobility and affluence. Early visitors called them the "Blue Men" of the Sahara. On the other hand, in the western hemisphere blue is associated with labor and the working class. It is the common color of overalls, blue jeans and other working costumes. Then again, someone with ‘blue blood’ can also be a member of the nobility. I find out the term comes from the Spanish sangre azul, and is said to refer to the pale skin and prominent blue veins of Spanish nobles. And, of course, blue is commonly used in Spain, as in several other cultures, to symbolize boys, in contrast to pink, which used for girls. It’s just that in the early 1900s, blue was the color for girls, since it had traditionally been the color of the Virgin Mary, while pink was for boys as it was akin to the color red considered a masculine color. I could go on. Ultramarine, cerulean, cobalt blue, Prussian blue… In ancient days blue thread was actually made from a dye extracted from a Mediterranean snail, hilazon, but the garment had to be exposed to the sun, the ultraviolet light, which transformed the more purple colorant to unadulterated blue. Most blue pigments were made from minerals though, especially lapis lazuli and azurite. It was crushed, grounded into powder and mixed with egg yolk and other binders - and made into striking rich blues of all shades and nuances. History can be gorgeous, subjected to the sun, the time, layer after layer, and eventually blended with contemporariness’. I acquire another blue gandora and stride the streets one more time, before taking the ferry back, across the blue Mediterranean Sea.. Sometimes when I watch my elderly neighbors laugh at a comment someone makes, or see them stop to kiss someone’s grandchild, I think of how much they have been through in their lives. So many years of struggle, with crops and with weather, so many long strenuous walks over the hills into town with hard earned produce, lack of doctors, lack of food, lack of paid work, sisters and brothers who died, fathers who where imprisoned, others who just left and never returned, not to mentions the wars. Some tragedies were larger than others. On the 6th of February, 1937, during the Spanish civil war, Malaga fell under control of the Franco army, which provoked a mass exodus of refugees from the city that fled to Almería by way of the coastal road. It is estimated that 150.000 people fled from Malaga that day. Well on the way they were systematically bombarded by Italian and German warships and aircraft, to such an extent that only some 30,000 actually made it to Almería. It is named the "Caravan of the Dead". The road goes by our coastal mountains. The common discovery of bones and other remains were reported into the 60s. Republicans who stayed behind in the provincial capital did not fare any better. Thousands of them were taken to areas like San Raphael Cemetery, shot, and left to rot in unmarked graves, and their families never heard from them again. The cemetery at San Raphael (close to the airport and now unused) is today, under the Zapatero government's Law of Historical Memory, the site of an exhumation of these bodies in attempt to bring some closure to still grieving families. The wounds of the past still remain close to the surface. None of this is talked a whole lot about among my neighbors. But I see that it is not forgotten - and I also see the desire for living your life as fully as you can, while you can. I have so much to learn. The Historical Memory Law, Ley de Memoria Histórica, is a Spanish law passed by the Congress of Deputies on the 31st of October 2007. It was based on a bill proposed by the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party government of Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. The Historical Memory Law principally recognizes the victims on both sides of the Spanish Civil War, gives rights to the victims and the descendants of victims of the Civil War and the subsequent dictatorship of General Francisco Franco, and formally condemns the Franco Regime. This photo is from Caravan of the Dead. It is originally by Norman Bethune, but re-photographed by me at el Centro de Exposiciones in Benalmádena, Spain, 2009. You can see more of them in the book, Norman Bethune, La Huella Solidaria. (see our shop)

Recently, I’ve learned that writer Miguel Cervantes wasn’t at all that successful early on in life. He had to try to make a living in all kinds other ways. He was a soldier. He was captured by Barbary pirates and sold as a slave in Algiers for 5 long years. He worked as a traveling government grain and oil collector. A couple of times he was jailed for financial reasons. Sometimes he wrote a lot, sometimes he despaired. He married, had no luck, divorced, had a daughter, and received three gun shot wounds in a fight, one of which caused major and permanent damage to his left hand. He moved on, looked for new jobs, new opportunities. (I have no idea why there hasn’t been a major movie produced about all he went through. There are many of us who could sympathize with him. In the 60s there was a b-movie released. Later it was retitled The Young Rebel, and went nearly unnoticed at the box office and did not do well critically.)

In the mid 1580s, he was 40 by then, Cervantes worked as a tax collector and lived in Velez-Malaga, just down the hill from us. It is likely Cútar was part of his jurisdiction. That meant he came up the road at times, knocked on people’s doors, invited himself in, had a chat, a glass of wine, and convinced those who owed money to pay off a sum. Apparently he was pretty good with people. Maybe he sat in our kitchen. Parts of the house most certainly stood here then. When Don Quixote was released, Cervantes was close to 60, and by the standards of the time, he must have seemed pretty old. He also must have had many memories of his stay around here, because Velez-Malaga is mentioned three times in the novel. When I was younger, I thought one would have it all figured out by the age of almost 60. Now I know better. I didn’t think I’d have a house that Cervantes possible visited either. I guess it’s of no use getting carried away by it all. “... he who's down one day can be up the next, unless he really wants to stay in bed, that is...” Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quixote Ancient European/Mediterranean Culture Alive in Málaga Today Verdiales is the name of the ancient frenetic folk music played in the mountains of Málaga. The fiesta of Verdiales, as it is called by those who play and take part in it, is a legacy of the magic, primitive, pagan, spiritual and joy in Mediterranean and European culture.

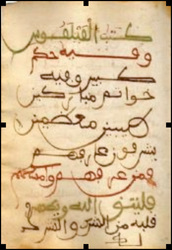

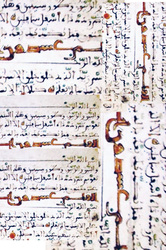

Its origins are rural, the history of which is difficult to ascertain because it has been handed down from generation to generation, lacking written documentation and historical references. Some authors, among them José María Caballero Bonald, say that the Fiesta is Archaic and Moorish in its origins. “The Fiesta of Verdiales is an Archaic musical monument, a cultural jewel of Málaga. More specifically, it is a sacred relic of a very remote Mediterranean past, which lives on in the music, song, dance and hats adorned with flowers linking the Fiesta of Verdiales with nothing less that the remotest religious cults of earth goddess and sun. Perhaps it’s greatest achievement is that it has been able to survive for millennia, stubbornly resisting successive invasions and colonization that have destroyed almost all signs of the ancient culture and history along the coast and mountains of Málaga. After the Visigoth invasion and colonization of the Byzantines, the Islamic colonization and subsequent conquest of the Christian Castilians, the only ancient signs of Malagueno history and identity that remain are its wine, raisins, small limed-white villages perched in its costal mountains and The Fiesta of Verdiales.” Although ancient elements exist in other strains of European folk music, the Fiesta of Verdiales seems to be the only multi-millennium rural music and dance in existence in Europe. If nothing else, unique as a country orchestra that has survived for Muhammad ben Ali al-Yayyar’s hopes came true when the three manuscripts he had hidden 500 years previously in a wall, supposedly in his home, were discovered when masons were working on the house on Calle Horno in the middle of the village of Cútar in June of 2003. Al-Yayyar had carefully encased the books in straw and mud and placed them in the niche in the wall later filling it to prevent it from sounding hollow when hit. This is his last entry: “The Lord of Castile broke the agreement and let baptize the people of Granada in the beginning of de yumadà al-ulà, which is equivalent to the middle of the month of duyanbir (december) of the year 905 (1500). Almighty God make them perish and treat them in a manner which only one who is decent and worthy is able to. It happened on a friday at dusk.” Muhammad ben Ali al-Yayyar, alfaquí, scholar of Islamic law, and imam of the mosque of Cútar, in la Axarquía of Málaga, must have sighed deeply. Something which gave a sign in some way of the pain and meloncholy that were produced by the thoughts that were envolved with scribing this note. It was included in his vademecum, manual and journal where he not only kept all of his legal references according to the laws of Islam that he would need in the function of alfaquí, but also many of the questions and observations he considered represented value to his Islamic culture. This culture that during 800 years had enriched the land of al-Andalus, but was successively reduced to the Nasarid Kingdom of Granada. After the seizure of the Guadalquivir valley, Jaén, Córdoba and Seville in the first half of the 13th century, the Nasarid Kingdom continued under constant threat of invasion from the Christian conquerors for another 250 years. This kingdom depended until that time on the cultivated slopes and terraces of Cútar and the neighboring villages. Its olives, and its vines which produced the most famous raisins in the world, in al-Yayyar’s day as well as today. It had been a month since the Catholic queen, Isabel of Castile, had ordered, under the council of Cardenal Cisneros, the ”general conversion” (forced) of the Mudejar of the kingdom which had been conquered a decade earlier. We don’t know for sure why al-Yayyar hid the books at that time, whether it was fear of being discovered as a Cryptomuslim, or whether he believed, as his fellow Jewish citizens believed 10 years earlier, that the circumstances surrounding their forced conversion would be temporary - That possibly in some 10 years or so the situation which had been the case centuries earlier would some how return to its natural course, that the followers of the three Semitic religions would once again coexist in al-Andalus. Land that once came from the Vandels and Visigoths, considered by the Arabs and Moor for centuries to be the anteroom to paradise. However, it didn’t turn out that, the intention of unifying everyone of Spain into one single faith was a fact. At this time it came to the realization of the Crypto-Jews, and not really much before. The Catholic monarchs began the expulsion, unique in the history of this country, and thereby the migration of the Hispanic Sefardim, taking with them their particular experience of al-Andalus to every corner of the Mediterranean, the Balkans, the Baltic and North Sea and the Americas. The Muslims however prepared to put into practice for the first time since the inception of the teachings of the Profet in Mecca, the Koranic doctrine of concealment which allowed them to remain in Spain for almost 100 years longer, pretending to be Christian but practicing Islam clandestinely After leaving the pen next to the inkwell, al-Yayyar, closed his book. He got up, taking the explanatory notes, his book on Islamic law and the family’s luxurious, polychromatic copy of the Koran and went to the top floor of the house, where he waited for his wife and children. There, just above the door on the ground floor, facing the courtyard, he had prepared a small cupboard. In that niche dug in the stone, gravel and mud wall he had put some earth and straw. Al-Yayyar placed the three books on the bed of straw and covered them with more straw, then with more earth. This way he filled the entire space so that, once refinished, the wall would not sound hollow. In this way he placed the books, which symbolically and materially meant fidelity to beliefs and a way of life that had been declared unwelcome in a land which had contributed to its cultural splendor for 781 years. In less than ten years, members of the al-Yayyar family had gone from being free Muslims in an Islamic state to being Muslim citizens subject to particularly restrictive legislation applied by the Christian government. That is to say they became Mudejares (domesticated Arab Muslim), later to end up as Moriscos, Moors, or Christians of Muslim origins and in most cases, secretly continued practicing their former religion. We do not know what happened later. Whether al-Yayyar and his family remained in Cútar, quietly preserving their Islamic loyalties until the general expulsion of the Moors from 1609-1612, or if their descendants stayed in Cútar, integrating with other new Christians to the mass of former Christians, and today, are the direct ancestors of some of the residents of this Cútar (Aquta) in the Axarquia. Or if, as did many of his coreligionists, once forcibly converted to Christianity chose to flee to North Africa in the hope, distant perhaps, of returning one day to be Muslims in a new al-Andalus. However, something did happen that al-Yayyar probably didn’t expect. In June 2003, the Santiago family was getting ready to remodel their house on C/ Horno in Cútar. It was quite a surprise for the builders and children who were watching the demolition of the wall facing the courtyard. After the sledge hammer had pounded the wall, there appeared between straw and earth, some books with strange script in a language foreign to the present inhabitants. As an aside, manuscripts of this kind are usually found by albañiles (masons). This Spanish word comes from the most important mathematician of western Arab world (al-Andalus magreb). His name was Al-Banna. There were three books found: The first was a book of trade, a book of reference, that as an alfarquí, Islamic scholar of law, al-Yayyar, consulted when he needed to clarify any particular case relative to his position. It includes parts of notarial forms, affidavits, inheritance rights, mathmatics, traditions of the Prophet and legal questions concerning marriage. It is well known that alfarquis were able to access once hidden Islamic power in the peninsula. Jurisdiction over certain civil cases, while there was a Moorish justice, they were in charge of administering, controlling donations to mosques and practically monopolizing the office of notary in Arabic. This book is of paper with some loose pages and slips of paper some of which some were folded. The book is bound in parchment. The second book, unlike the previous, was more personal. This is where Muhammad al-Yayyar gives us data and dates of his life and his community, but there are poems contained prophetic invocations, sermons, hadith and other chapters of religious, magic and esoteric character. It was his vademecum or journal. This book is also of paper with inserted loose pages. The parchment cover has geometric designs. The back cover has tree type of Arabic script, possibly an earlier document later used to bind the book. Because the books were not reported the the Malaga Archive during the first week after their discovery, we don’t know if the placement of these loose pieces were of any significance. The third book is a copy of the Koran, necessary and essential for every Muslim and therefore, for a alfaqui, faqih. This is certainly the family Koran, and is the oldest of the documents, since it was, in the time of al-Yayyar, more than a century old, being from the 14th century. It is was scribed with several colors of ink and, unfortunately, is incomplete because it lacks a few final pages, which really doesn’t matter so much due to its great historical importance. The Andalusian government financed the production facsimile editions. One of which was given to king Mohammed VI of Morocco, another will be housed in the Monfí Museum in Cútar. Al-Yayyar was not able to retrieve his books, but their cultural successors, those who have found them, understand the significance that they must have had for him. We now have them to use and to treat them with due respect and appreciation. We can say then that al-Yayyar’s hope have been fulfilled in that his lost books together with his memories and those of his people are now preserved for the benefit of everyone. The source of the information used for this article is from the study by Maria Isabel Calero Secall, “Los manuscritos árabes de Málaga: Los “libros” de un alfaquí de Cútar del s. XV”, Nicolás Roser Nebot, Departamento de Traducción Monfi festival: Music, food and sweets of Al-Andalus, lectures on Andalusian culture and the three Arab language manuscripts found in Cútar, are some of the highlights included in the program of the two-day 2011 Monfí Festival in Cútar, Axarquia, this 8-9 October 2011. For more info, or for info on how to get there and where to stay; please contact laCultura

|

Categories

|

laCultura.cc

RSS Feed

RSS Feed