Al-Yayyar had carefully encased the books in straw and mud and placed them in the niche in the wall later filling it to prevent it from sounding hollow when hit.

This is his last entry:

“The Lord of Castile broke the agreement and let baptize the people of Granada in the beginning of de yumadà al-ulà, which is equivalent to the middle of the month of duyanbir (december) of the year 905 (1500). Almighty God make them perish and treat them in a manner which only one who is decent and worthy is able to. It happened on a friday at dusk.”

Muhammad ben Ali al-Yayyar, alfaquí, scholar of Islamic law, and imam of the mosque of Cútar, in la Axarquía of Málaga, must have sighed deeply. Something which gave a sign in some way of the pain and meloncholy that were produced by the thoughts that were envolved with scribing this note. It was included in his vademecum, manual and journal where he not only kept all of his legal references according to the laws of Islam that he would need in the function of alfaquí, but also many of the questions and observations he considered represented value to his Islamic culture. This culture that during 800 years had enriched the land of al-Andalus, but was successively reduced to the Nasarid Kingdom of Granada. After the seizure of the Guadalquivir valley, Jaén, Córdoba and Seville in the first half of the 13th century, the Nasarid Kingdom continued under constant threat of invasion from the Christian conquerors for another 250 years. This kingdom depended until that time on the cultivated slopes and terraces of Cútar and the neighboring villages. Its olives, and its vines which produced the most famous raisins in the world, in al-Yayyar’s day as well as today.

It had been a month since the Catholic queen, Isabel of Castile, had ordered, under the council of Cardenal Cisneros, the ”general conversion” (forced) of the Mudejar of the kingdom which had been conquered a decade earlier. We don’t know for sure why al-Yayyar hid the books at that time, whether it was fear of being discovered as a Cryptomuslim, or whether he believed, as his fellow Jewish citizens believed 10 years earlier, that the circumstances surrounding their forced conversion would be temporary - That possibly in some 10 years or so the situation which had been the case centuries earlier would some how return to its natural course, that the followers of the three Semitic religions would once again coexist in al-Andalus. Land that once came from the Vandels and Visigoths, considered by the Arabs and Moor for centuries to be the anteroom to paradise.

However, it didn’t turn out that, the intention of unifying everyone of Spain into one single faith was a fact. At this time it came to the realization of the Crypto-Jews, and not really much before. The Catholic monarchs began the expulsion, unique in the history of this country, and thereby the migration of the Hispanic Sefardim, taking with them their particular experience of al-Andalus to every corner of the Mediterranean, the Balkans, the Baltic and North Sea and the Americas.

The Muslims however prepared to put into practice for the first time since the inception of the teachings of the Profet in Mecca, the Koranic doctrine of concealment which allowed them to remain in Spain for almost 100 years longer, pretending to be Christian but practicing Islam clandestinely

After leaving the pen next to the inkwell, al-Yayyar, closed his book. He got up, taking the explanatory notes, his book on Islamic law and the family’s luxurious, polychromatic copy of the Koran and went to the top floor of the house, where he waited for his wife and children. There, just above the door on the ground floor, facing the courtyard, he had prepared a small cupboard. In that niche dug in the stone, gravel and mud wall he had put some earth and straw. Al-Yayyar placed the three books on the bed of straw and covered them with more straw, then with more earth. This way he filled the entire space so that, once refinished, the wall would not sound hollow. In this way he placed the books, which symbolically and materially meant fidelity to beliefs and a way of life that had been declared unwelcome in a land which had contributed to its cultural splendor for 781 years.

In less than ten years, members of the al-Yayyar family had gone from being free Muslims in an Islamic state to being Muslim citizens subject to particularly restrictive legislation applied by the Christian government. That is to say they became Mudejares (domesticated Arab Muslim), later to end up as Moriscos, Moors, or Christians of Muslim origins and in most cases, secretly continued practicing their former religion.

We do not know what happened later. Whether al-Yayyar and his family remained in Cútar, quietly preserving their Islamic loyalties until the general expulsion of the Moors from 1609-1612, or if their descendants stayed in Cútar, integrating with other new Christians to the mass of former Christians, and today, are the direct ancestors of some of the residents of this Cútar (Aquta) in the Axarquia. Or if, as did many of his coreligionists, once forcibly converted to Christianity chose to flee to North Africa in the hope, distant perhaps, of returning one day to be Muslims in a new al-Andalus.

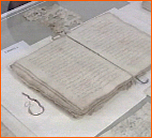

However, something did happen that al-Yayyar probably didn’t expect. In June 2003, the Santiago family was getting ready to remodel their house on C/ Horno in Cútar. It was quite a surprise for the builders and children who were watching the demolition of the wall facing the courtyard. After the sledge hammer had pounded the wall, there appeared between straw and earth, some books with strange script in a language foreign to the present inhabitants.

As an aside, manuscripts of this kind are usually found by albañiles (masons). This Spanish word comes from the most important mathematician of western Arab world (al-Andalus magreb). His name was Al-Banna.

There were three books found:

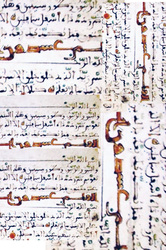

The first was a book of trade, a book of reference, that as an alfarquí, Islamic scholar of law, al-Yayyar, consulted when he needed to clarify any particular case relative to his position. It includes parts of notarial forms, affidavits, inheritance rights, mathmatics, traditions of the Prophet and legal questions concerning marriage.

It is well known that alfarquis were able to access once hidden Islamic power in the peninsula. Jurisdiction over certain civil cases, while there was a Moorish justice, they were in charge of administering, controlling donations to mosques and practically monopolizing the office of notary in Arabic.

This book is of paper with some loose pages and slips of paper some of which some were folded. The book is bound in parchment.

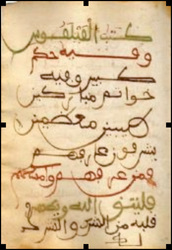

The second book, unlike the previous, was more personal. This is where Muhammad al-Yayyar gives us data and dates of his life and his community, but there are poems contained prophetic invocations, sermons, hadith and other chapters of religious, magic and esoteric character. It was his vademecum or journal.

This book is also of paper with inserted loose pages. The parchment cover has geometric designs. The back cover has tree type of Arabic script, possibly an earlier document later used to bind the book. Because the books were not reported the the Malaga Archive during the first week after their discovery, we don’t know if the placement of these loose pieces were of any significance.

The third book is a copy of the Koran, necessary and essential for every Muslim and therefore, for a alfaqui, faqih. This is certainly the family Koran, and is the oldest of the documents, since it was, in the time of al-Yayyar, more than a century old, being from the 14th century. It is was scribed with several colors of ink and, unfortunately, is incomplete because it lacks a few final pages, which really doesn’t matter so much due to its great historical importance. The Andalusian government financed the production facsimile editions. One of which was given to king Mohammed VI of Morocco, another will be housed in the Monfí Museum in Cútar.

Al-Yayyar was not able to retrieve his books, but their cultural successors, those who have found them, understand the significance that they must have had for him. We now have them to use and to treat them with due respect and appreciation.

We can say then that al-Yayyar’s hope have been fulfilled in that his lost books together with his memories and those of his people are now preserved for the benefit of everyone.

The source of the information used for this article is from the study by Maria Isabel Calero Secall, “Los manuscritos árabes de Málaga: Los “libros” de un alfaquí de Cútar del s. XV”,

Nicolás Roser Nebot, Departamento de Traducción

RSS Feed

RSS Feed