Archeology in Rome testifies to the size of the Andalucian olive oil industry for the empire.

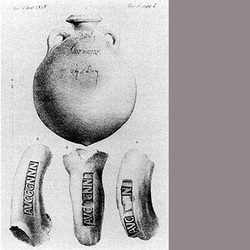

Monte Testaccio is a waste mound in Rome where almost exclusively Spanish oil amphorea were discarded during the first 250 yrs of the first milennium of the common era. The hill was constructed using mostly the fragments of large globular 70-litre (15 imp gal; 18 U.S. gal) vessels from Baetica (the Guadalquivir and costal region of Andalucía in modern Spain), of a type known as Dressel 20.

It is not clear why Monte Testaccio was built using only olive oil vessels. The oil itself was probably decanted into bulk containers when the amphorae were unloaded at the port, in much the same way as other staples such as grain. There is no equivalent mound of broken grain or wine amphorae and the overwhelming majority of the amphorae found at Monte Testaccio are of one single type, which raises the question of why the Romans found it necessary to dispose of the amphorae in this way.

One possibility is that the Dressel 20 amphora, the principal type found at Monte Testaccio, may have been unusually difficult to recycle. Many types of amphora could be re-used to carry the same type of product or modified to serve a different purpose—for instance, as drain pipes or flower pots. Fragmentary amphorae could be pounded into chips to use in opus signinum, a type of concrete widely used as a building material, or could simply be used as landfill. The Dressel 20 amphora, however, broke into large curved fragments that could not readily be reduced to small sherds. It is likely that the difficulty of reusing or repurposing the Dressel 20s meant that it was more economical to discard them.

Monte Testaccio has provided archaeologists with a rare insight into the ancient Roman economy. The amphorae deposited in the mound were often labelled with tituli pictii, commercial inscriptions painted or stamped, which record information such as the weight of the oil contained in the vessel, the names of the people who weighed and documented the oil and the name of the district where the oil was originally bottled. This has allowed archaeologists to determine that the oil in the vessels was imported under state authority and was designated for the annona urbis (distribution to the people of Rome) or the annona militaris (distribution to the army). Indeed, some of the inscriptions found on mid-2nd century vessels at Monte Testaccio specifically record that the oil they once contained was delivered to the praefectus annonae, the official in charge of the state-run food distribution service. It is possible that Monte Testaccio was also managed by the praefectus annonae.

The tituli picti on the Monte Testaccio amphorae tend to follow a standard pattern and indicate a rigorous system of inspection to control trade and deter fraud. An amphora was first weighed while empty, and its weight was marked on the outside of the vessel. The name of the export merchant was then noted, followed by a line giving the weight of the oil contained in the amphora (subtracting the previously determined weight of the vessel itself). Those responsible for carrying out and monitoring the weighing then signed their names on the amphora and the location of the farm from which the oil originated was also noted. A stamp on the vessel’s handle often identified the maker of the amphora.

The inscriptions also provide evidence of the structure of the oil export business. Apart from single names, many inscriptions list combinations such as "the two Aurelii Heraclae, father and son", "the Fadii", "Cutius Celsianus and Fabius Galaticus", "the two Junii, Melissus and Melissa", "the partners Hyacinthus, Isidore and Pollio", "L. Marius Phoebus and the Vibii, Viator and Retitutus." This suggests that many of those involved were members of joint enterprises, perhaps small workshops involving business partners, father-son teams and skilled freedmen.

Later Monte Testaccio’s economic significance was somewhat greater, as the hill's interior was discovered to have unusual cooling properties which investigators attributed to the ventilation produced by its porous structure. This made it ideal for wine storage and caves were excavated to keep wine cool in the heat of the Roman summer.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed