Phoenician colonies on the coast of Málaga

Except for only small portions and some photos, most of this article is a summary of Aubet, Maria Eugenia, The Phoenicians and the West, Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed. 200l

by Rudy Vigil

.

The Phoenicians, also known as the Canaanites, were a northern Semitic civilization from what is today primarily Lebanon in the eastern Mediterranean. They were made up of city-states, Ugarit, Byblos, Sidon, Berytus, Tyre, etc., located on small points or islands very close to the coast for protection and easy access to the sea. This is a settlement pattern that is reflected later in Andalucía as well as Ibiza, Sardinia, Malta and Carthage.

At times the Phoenicians had control of the Levant inland, as far as Syria and Jordan, from where they cultivated natural resources. However, during the 12th century BC there were a invading people know in ancient writings as the “Sea People”, possibly the Minoans. Along with other upheavals the Phoenicians were forced to seek resources elsewhere, eventually developing a maritime trading culture that expanded their influence from the Levant to North Africa, Greek Isles, Sicily, and the Iberian Peninsula. The

Phoenician expansion into the Mediterranean

Our knowledge of the Phoenicians is scant. Ancient documentation seems to date inaccurately, but archeological finds during the last 40 yrs especially on the coast of Málaga and Granada have given us a better picture.

On the Iberian Peninsula Phoenicians found the Tartessos and the metals, silver, iron, tin and lead, from some of which they could craft exquisite vessels and figurines. A monetary system had not yet developed, so that these luxury items were the means of trade for other goods and often in the form of tribute and gifts. Phoenician religion centered usually on city deities. Along with Baal (Lord), Melqart (Hercules) and Astarte (Aphrodite) in Tyres, whose elite class were responsible for western expansion in the Mediterranean, were also a major elements of trade. Tribute being offered to Melqart in the temple near Gadir (Cádiz) the port which the Phoenicians established near the Tartessos and the mines of Río Tinto, beyond the pillars of Hercules (the strait of Gibraltar). Cádiz is thought to be the oldest continually inhabited city in Europe, some 2,700 yrs.

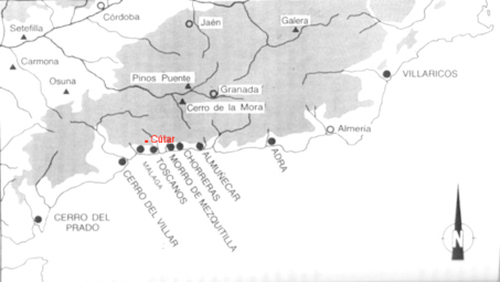

The sources of information for Phonician colonies of eastern Andalucía are different from those for Gadir (Cádiz) due to the lack of ancient documentation. Knowledge of the settlements from Málaga to Villaricos in Almería has been one of the biggest surprises of Phoenician archaeology in recent times. This region like Ibiza, was practically unknown to classical historiography and even erroneously linked by a few classical authors to Greek or Carthaginian colonization. Today it constitutes one of the most spectacular and ancient archaeological clusters known in the western Mediterranean and its discovery has given an unexpected turn to the study of the Phoenicians in the west.

The strait of Gibraltar was often difficult to navigate at various times of the year, making it necessary to wait on the coast of Málaga before being able to pass into the Atlantic and the Port of Gadir. It is thought that for this reason many Phoenician settlements were established on the coast of Málaga. The distance between these Phoenecian establishments were surprisingly short. It is possible that the building boom along the coast of Málaga during the 70s, however, destroyed some sites. For example in Fuengirola and Rincon de la Victoria located west and east of Málaga respectively. Cerro del Vellar, was situated at the mouth of the Guadalhorce. 4 km west from Malaka (the site of present Málaga). Toscanos, 27 km east of Malaka, was at the mouth of the Río Vélez and the watershed in which Cútar is located. 7 km further east was Morro de Mezquitilla and the necropolis of Trayamar at the mouth of the Río Algarrobo. 800 m from Morro was Chorreras and it’s necropolis in Lagos. Sexi, today’s Almuñécar, which was also the site of a necropolis, was 30 km east of Lagos.

It is not easy to determine the causes of objectives for such a high population. Their relationship with Gadir is difficult to assess as well. As mentioned the maritime factors could have caused any ship making for Gadir to drop anchor on this precise stretch of coastline. But this reason alone does not justify a density of such stable and permanent Phoenician installations.

The wealth of archaeological documentation recorded at some of the sites like Toscanos, or the sumptuous nature of the Phoenician necropolises at Trayamar or Almuñecar have occasionally led to the importance of these Phoenician establishments being exaggerated, overlooking the cultural and economic weight of Gadir on the Atlantic coast. Although it is said that Gadir was 10 ha., while Toscanos was extended from 2,5 ha. in the 8th century to 12-15 ha. by the 7th.

These recent archaeological finds, Greek imported ceramics as well as those produced in Tyre and on site, have established that the settlements must have been founded around the middle of the 8th century BC, Morro de Mezquitilla being the earliest, established at about the same time as Gadir, Carthage and in Sardinia.

Evidence indicated that Morro de Mezquitilla shows a small port installation, and judging by the category and the luxury of the earliest dwellings, relatively high-ranking eastern people may have lived there – merchants, perhaps, or businessmen – together with artisans and metallurgists who operated in accordance with the internal needs of the population. The find of a district of metal workshops does not just indicate the industrial and mercantile character of these first trading posts, it reveals, too, the existence of one of the most ancient iron metallurgies known in western Europe.

The majority of the Phoenician enclaves, however, seem to have arisen in the second half of the 8th century BC. This is true of

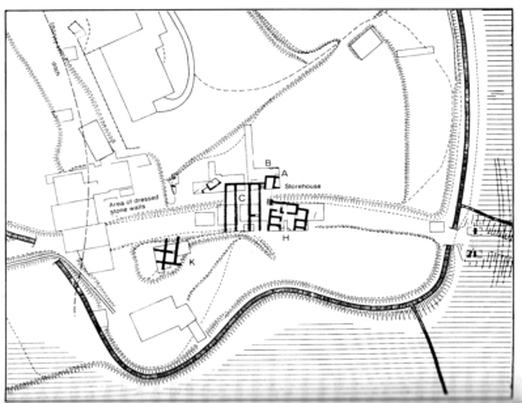

Map of Phoenician site at Toscanso

Toscanos was founded around the years 730-720 BC, judging by the earliest pottery of classical Tyrian forms. The settlement dominated the plain of the river Vélez and the important maritime bay. There they built several large isolated dwellings (building A), bounded by streets or paths similar to those of the contemporary Chorreras. After this initial phase, the settlement experienced considerable growth with new Luxury dwellings being built (buildings H and K). During this second phase, still dated to the 8th century, a tendency towards urban agglomeration is observed, possibly in response to a 2nd wave of colonists, particularly notable being the construction of up-market houses, a phenomenon observed at the same time in Morro de Mezquitilla and Chorreras. In other words, the earliest architecture on these sites marks the arrival of family groups or individuals of a fairly high economic standard.

Around the year 700 BC, an important qualitative leap is observed which finally determines the economic character of the center and is paralleled by similar changes taking place on the Algorrobo. An enormous building with three aisles and apparently two

View from a top the cliff Peñón of Tocanos (Phoencian wall) and the site of the necropolis at Cerro del Mar at the mouth of the Río Vélez with close-by settlements of Morro de Mezquitilla and Chorreras in the distance.

In the East, a warehouse for merchandise, containing grain, oil or wine was the characteristic structure of every marketing center or geographic concentration of commercial transactions, and in general was the forerunner of a market system. The marketplace

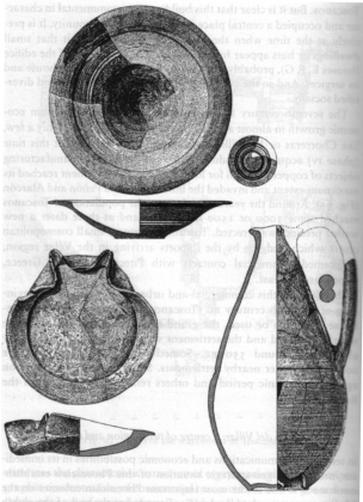

Red-slip pottery from Toscanos (8th – 7th centuries BC)

Bronze thymiaterion (a type of ritual incense burner) form Cerro del Peñón

Shortly after this commercial and urban highpoint, at the beginning of the 6th century BC, the great central warehouse ceased to be used, the grand residences of the town center were abandoned and the settlement was reorganized, to be finally abandoned around 550 BC. Something similar seems to have occurred in other nearby settlements. Some came into occupation again in the Punic period and others remained in ruins until the Roman period.

Cerro del Vellar: a center of production and trade

In terms of communications and economic possibilities in its immediate interior, the geo-strategic situation of this Phoenician establishment made it one of the most important Phoenician colonies on the Mediterranean coast of Andalucía. Founded

Here at Cerro del Villar at the mouth of the Guadalhorce you can see present day Málaga in the background. Livesstock were raised extensively by the Phoenicians. photo Helen Vigil

At the delta of the river Guadalhorce studies reveal a landscape, in the Phoenician period, of riverside woods and marshes around the island, subject to successive sea and freshwater floods due to the alluvial silting of the valley; a phenomenon that ultimately forced the Phoenicians to abandon the site and found Malaka. The degradation of the surroundings and of the forest cover, and the consequent erosion of the soil throughout th 7th and 6th centuries, shown in pollen diagrams, was due to the intense cropping, stock raising and logging activities undertaken by the Phoenicians of Villar.

The colony’s catchment area for resources is estimated at some 18 km2. The territory was made up of the alluvial soils of the valley, suitable for irrigation agriculture and lowland pasture, and also of clay outcrops of excellent quality which could be exploited for industrial and handicraft purposes.

Research shows intensive animal husbandry, based mainly on grazing larger livestock such as pigs, goats and sheep. Extensive cropping in the zone during the 7th and 6th centuries, with notable quantities of wheat and barley, as well as the production and marketing of wine; this coincides with the decline in the woodlands of the interior.

The 7th century levels of stratification correspond to the period of greatest commercial and industrial activity in the Phoenician colony. Rectangular dwellings covered with flat roofs of beaten clay supported on wooden beams were separated by wide streets and bounded occasionally by small landing-piers. Outstanding among the local activities most characteristic of the 7th century are

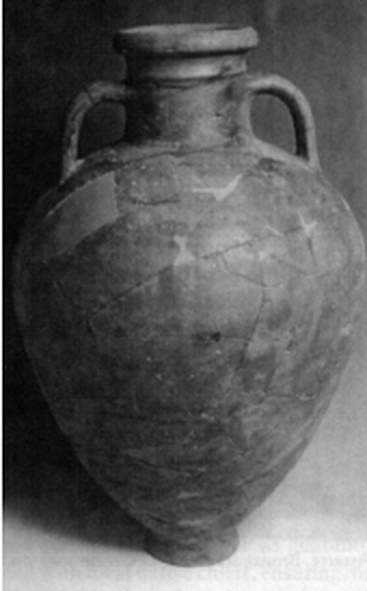

Greek ‘SOS’-type amphora from Cerro del Villar (7th cen)

The indigenous and Phoenician colonial trade.

The meager dimensions of the colonial settlements in eastern Andalucía and the small size of their necropolises suggest that the Phoenician population in this area must have been fairly limited. That means that a great deal of the activity that developed in the ports, the farmland and the industry was the responsibility of the native population.

Until recently the dominant view was that the Phoenicians had settled in a territory with an exceedingly sparse indigenous population, scattered in small hamlets along the valleys and mountainsides. The archaeological evidence of the past few years demonstrates, on the contrary, the presence of important nuclei of indigenous people, established since the Middle and Final Bronze Age at strategic sites dominating the main communication routes to the interior of the provinces of Málaga and Granada.

The Phoenician establishments on the coast of Málaga and Granada initiated commercial exchanges with the indigenous very early on. This is inferred from the presence, from the 2nd half of the 8th century BC, of amphorae and imported articles in the native townships of the upper Guadalhorce and the vega of Granada, etc. Phoenician amphorae in these zones reflects a trade in oil or wine with the interior, although in most cases it is not known what the economic rewards were.

The example of the valley of Vélez, where there was the important Final Bronze Age settlement, Vélez-Málaga – a strategic watchtower dominating the river passage to the interior and, consequently, to Toscanos itself – demonstrates the extent to which Phoenician trade depended on agreements or pacts with a few communities that dominated interregional trade, the territory, the lines of communication and their own resources. So, it is likely that the Phoenicians restricted themselves to exploiting a few trading circuits already in existence, reorganizing them for their own profit and availing themselves of the experience of a population with a long tradition of long-distance trade. In return, the colonial trade could consolidate the status and political power of the native chiefs in the interior, enabling them to import and control exotic or luxury goods and transform their seats into genuine centers of political and economic control.

In general, Phoenician trade promoted an intensification of the exploitation of raw materials – mining, agriculture and grazing – through intensive use of resources, at the same time as it fostered in particular territories the production of goods for commerce and consumption, and a demand for formerly non-existent products. Large-scale commercialization of agricultural products and, of course, supplying a workforce and subsistence goods to the coast must have generated important changes in the socio- political organization of the indigenous communities on the periphery of the colonies.

In summing up, according to Aubet, a study of the interrelations between a colonial system and the indigenous world in terms of exclusively “acculturation” and “orientalization”, as has been done until now, is completely inadequate. When speaking of the interaction of unequal communities and economics, consideration must be given not only to cultural exchange, the spread of information and technology, or trade, but also, and above all, to the forms of integration, adaptation, resistance and exploitation generated by the cultural encounter of two disparate societies. It must be said that the history of this cultural encounter cannot be written exclusively in colonial terms but rather from a bilateral, overall view.

Rudy Vigil

Except for only small portions and some photos, most of this article is a summary of Aubet, Maria Eugenia, The Phoenicians and the West, Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed. 200l

RSS Feed

RSS Feed